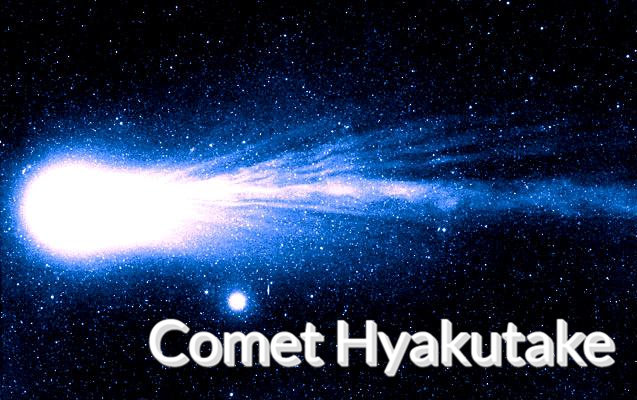

Comet Hyakutake, a long-period comet, was discovered by amateur astronomer Yuji Hyakutake in 1996. It rapidly brightened in the night sky, displaying a stunning bluish-green tail and coming as close as 0.1 astronomical units to Earth, making it a prominent celestial object.

Beyond its visual spectacle, the unexpected encounter between Comet Hyakutake and the Ulysses spacecraft in 1996 provided astronomers with valuable insights, revealing the comet’s characteristics and confirming its tail as one of the longest ever observed. Here is a detailed introduction to Comet Hyakutake:

Features of Comet Hyakutake

Comet Hyakutake is a long-period comet, with an orbital period of over 200 years. It was the first comet observed to emit X-rays, a phenomenon unexpected by astronomers.

The comet was discovered by Yuji Hyakutake on January 30, 1996, and it made its closest approach to Earth on March 25, 1996, at a distance of approximately 1.35 million kilometers. It also passed its perihelion on May 1 of the same year.

Initially, when it was discovered, the comet was near the orbit of Mars, and it had low brightness. However, by March, its brightness rapidly increased from an initial magnitude of 11 to a peak brightness of -0.3, making it visible to the naked eye. This dramatic change occurred in just about three months. The comet had a distinctive bluish-green head, and by the end of March, it had a tail that stretched up to 120 degrees, spanning from the Big Dipper to half of the night sky, creating a spectacular sight for many amateur astronomers. The structure of the comet was solid, with its size rapidly increasing from the initial 2.5 arcminutes to about 90 degrees at the peak. After several months of rapid growth, it quickly disappeared from the night sky, leaving astronomers and the general public captivated.

What made Comet Hyakutake even more intriguing was the discovery that, from March 26 to 28, astronomers in the United States and Germany observed X-ray emissions from the comet using the Rosat X-ray satellite. The origin of the comet’s X-rays remains a subject of study and debate. Researchers are uncertain if they originated from within the comet or as a result of intense interactions with the solar wind and comet’s material. This discovery introduced new avenues of research and investigation for astronomers.

Discovery by Yuji Hyakutake

The central figure in the world of comets in 1996 was Yuji Hyakutake, a Japanese amateur astronomer. He worked in a newspaper’s photolithography department and lived with his family in the town of Hayato, southwest of Tokyo. Due to severe light pollution and air pollution in his hometown, he decided to move to Kagoshima, a place with clearer and darker skies, two and a half years before the discovery.

Of the two comets Hyakutake discovered, the first one, C/1995 Y1, was relatively dim, with a maximum magnitude of 7.8, making it hard to see with small telescopes. The second one, C/1996 B2, was much brighter and became famous as Comet Hyakutake. The term “Comet Hyakutake” typically refers to the second comet, which brought him worldwide recognition.

Hyakutake’s interest in comets was piqued in 1965 when he witnessed Comet Ikeya-Seki, a well-known comet in Japan at the time. His passion for comets led him to start searching for them in 1989. However, it was only after he moved to his new home two and a half years before the discovery that he began a dedicated and serious search for comets. He used a 25×150 Fujinon binocular telescope with a tracking mount and would spend about four nights a month, from 2:00 AM to 5:00 AM, searching the sky at a location 15 kilometers away from his home, eagerly hoping to spot the trail of a comet.

His efforts finally paid off on Christmas Day in 1995 when he discovered his first comet, C/1995 Y1. This discovery was significant for his astronomical journey, and it followed the formal naming convention for comets, with “C” indicating it as a comet, “1995” representing the year of discovery, “Y” signifying the second half of December (since “I” is omitted), and “1” indicating it was the first comet discovered during that half of the month. The comet was also colloquially named Comet Hyakutake, using the discoverer’s last name or first name.

Discovery of Hyakutake II

Five weeks later, he discovered his second comet, C/1996 B2, which would also make him globally famous as Comet Hyakutake.

In January 1996, Yuji Hyakutake encountered a whole month of unfavorable weather conditions, and on January 30, he headed out with the hope that the skies would clear after the moon had set at around 3:30 in the early morning. By about 4:00 AM, when the sky had indeed cleared, he intended to observe his first comet, C/1995 Y1, and simultaneously keep two other celestial objects, M101 and NGC5474, in the field of view of his binocular telescope. At that time, C/1995 Y1 had an approximate magnitude of 9 and a diameter of about 8 arcminutes, slightly smaller than M101. About 20 minutes later, as he passed by the constellation Corvus, he “accidentally” glimpsed a comet-like object through a gap in the clouds. Because this region of the sky was very close to C/1995 Y1, and Hyakutake frequently observed C/1995 Y1 in this area, he was very familiar with the stars in this part of the sky. Incredulously, he muttered to himself, “I must be dreaming!” After a moment of calm, at around 4:50 AM, he began to sketch the relative positions of this comet-like object compared to the other stars in the background. This comet-like object had a more solid structure than C/1995 Y1, was only about magnitude 11 bright, and had a diameter of approximately 2.5 arcminutes. By 5:40 AM, as the sky was getting brighter, he recorded the object’s relative position again, confirming that it was moving. He believed this “might be a comet” and was heading toward Earth. He hurried back home to check the existing records of discovered comets, but he couldn’t find any that were moving toward the Corvus constellation. He then drafted a report and sent it to the National Astronomical Observatory in Tokyo and comet orbit expert Syuichi Nakano. Around 3:00 AM the next day, Nakano sent a fax to Yuji Hyakutake, confirming that the celestial object was indeed a new comet.

Orbital and Visual Characteristics

Comet Hyakutake’s orbital calculation: Scientists calculated the orbit of this comet for the first time and realized that it would come closest to Earth on March 25, 1996, at a distance of only 0.1 astronomical units (AU). In the previous century, only four comets had come closer to Earth. Due to this proximity, Comet Hale–Bopp was being discussed as a possible “great comet,” and the astronomical community eventually realized that Hyakutake might also become spectacular.

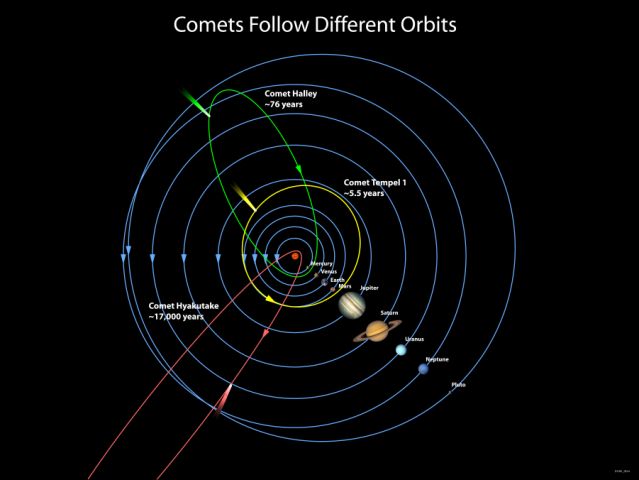

Distinctive features of Comet Hyakutake’s orbit: The comet’s orbital characteristics indicated that it had last visited the inner solar system approximately 17,000 years ago. Given its probable previous close encounters with the Sun, the 1996 approach was not its first visit from the Oort cloud, a region where comets with orbital periods of millions of years originate. Comets entering the inner solar system for the first time may brighten rapidly as they approach the Sun due to the evaporation of highly volatile materials. This phenomenon was observed with Comet Kohoutek in 1973, initially thought to be potentially spectacular but ultimately appearing only moderately bright. Older comets, however, exhibit a more consistent pattern of brightening. Therefore, all indications suggested that Comet Hyakutake would be exceptionally bright.

Unique observation opportunity: In addition to its close approach to Earth, the comet would be visible throughout the night for northern hemisphere observers due to its path, which took it very close to the pole star. This was an unusual occurrence because most comets appear in the sky near the Sun when they are at their brightest, resulting in comets being visible in a sky that is not completely dark.

Hyakutake’s Grand Journey

Comet Hyakutake became visible to the naked eye in early March 1996, and it rapidly brightened as it approached Earth, accompanied by an extension of its tail.

Visible in Early March: Comet Hyakutake became visible to the naked eye in early March 1996. However, initially, it was fairly unremarkable, with a brightness of approximately magnitude 4 and a tail about 5 degrees long.

Rapid Brightening: As it neared its closest approach to Earth, it rapidly became brighter, and its tail grew longer. By March 24, it had become one of the brightest objects in the night sky, with a tail stretching 35 degrees and displaying a distinct bluish-green color.

Closest Approach to Earth: The closest approach occurred on March 25, with the comet reaching a distance of 0.1 astronomical units (AU), approximately 15 million kilometers (39 lunar distances) from Earth. The comet’s motion across the night sky was so swift that its movement against the background stars could be detected in just a few minutes, covering the diameter of a full moon (half a degree) every 30 minutes. Observers estimated its magnitude to be around 0, and reported tail lengths of up to 80 degrees. Its coma, now close to the zenith for observers at mid-northern latitudes, appeared to be approximately 1.5 to 2 degrees in diameter, roughly four times the diameter of the full moon.

Bluish-Green Appearance: The comet’s head displayed a distinctly bluish-green color, possibly due to emissions from diatomic carbon (C2) combined with sunlight reflected from dust grains.

Short-Lived Brightness: Comet Hyakutake’s brightest phase lasted only a few days, and it did not capture the public’s imagination to the extent that Comet Hale–Bopp did the following year. Unfavorable weather conditions meant that many European observers, in particular, did not get to witness the comet at its peak.

Ulysses Spacecraft’s Mysterious Encounter with Hyakutake

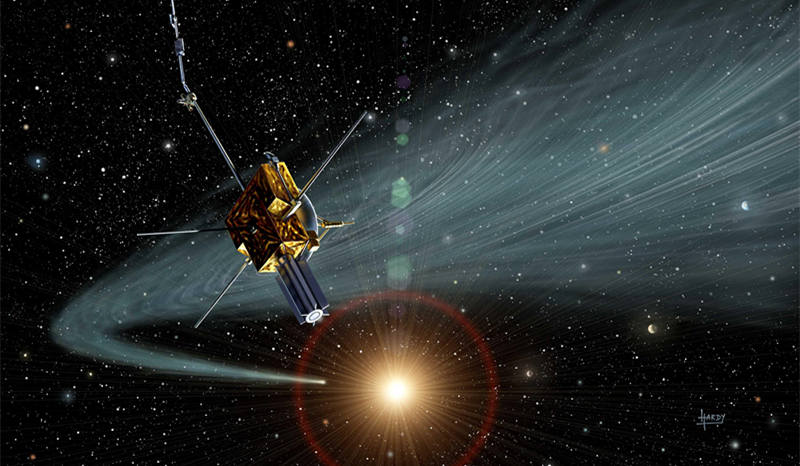

On May 1, 1996, the Ulysses spacecraft unexpectedly crossed the tail of Comet Hyakutake. However, the evidence of this encounter was not noticed until 1998.

Discovery of Evidence: Astronomers analyzed old data and found that Ulysses’ instruments had detected a significant decrease in the number of protons passing through, as well as changes in the direction and strength of the local magnetic field. This suggested that the spacecraft had crossed the “wake” of an object, most likely a comet, although the specific object responsible was not immediately identified.

Confirmation of Hyakutake: In 2000, two independent teams analyzed the same event. The magnetometer team realized that the changes in the magnetic field direction matched the “draping” pattern expected in a comet’s ion or plasma tail. Further investigation led them to discover that Comet Hyakutake had crossed Ulysses’ orbital plane on April 23, 1996.

Chemical Composition: Another team, working with data from the spacecraft’s ion composition spectrometer, detected a sudden large increase in ionized particle levels at the same time. The relative abundances of chemical elements detected confirmed that the object responsible was indeed a comet.

Comet Tail Length: Based on the Ulysses encounter, it was determined that Comet Hyakutake’s tail was at least 570 million kilometers (360 million miles or 3.8 AU) long, nearly double the length of the previously longest-known cometary tail from the Great Comet of 1843, which measured 2 AU. However, this record was later broken in 2002 by Comet 153P/Ikeya–Zhang, which had a tail length of at least 7.46 AU.

END:

Comet Hyakutake’s spectacular visit to our night sky in 1996 left a lasting impression on astronomers and skywatchers alike. While this particular comet has completed its journey and is no longer visible, the legacy of its extraordinary display continues to fuel anticipation for future comet sightings.

The future holds the promise of more remarkable cometary encounters. Scientists and amateur astronomers eagerly await the next celestial visitor from the distant corners of our solar system. Each comet that graces our skies brings with it the potential for new discoveries, unexpected phenomena, and captivating visuals. Whether through advanced telescopes or spacecraft missions, future comets like Hyakutake offer opportunities to gain deeper insights into the composition, behavior, and origins of these enigmatic cosmic wanderers.

Comet Hyakutake’s awe-inspiring passage reminds us that the cosmos continues to hold secrets waiting to be unveiled. In the coming years and decades, we can look forward to more opportunities to witness and study these celestial marvels, and who knows what wonders the next great comet will bring to our night skies. As the universe unfolds, we anticipate that the legacy of Comet Hyakutake will inspire generations of stargazers to come, keeping our eyes fixed on the heavens in hopes of future celestial surprises.

More UFOs and mysterious files, please check out our YouTube channel: MysFiles

Lacerta Files: Human beings are the product of genetic engineering by alien civilizations.